Bangladesh responds to the Rohingya refugee crisis

I recently traveled to Bangladesh on an assignment to meet with Rohingya refugees who, for the past 30 years, have been fleeing persecution in their home country Myanmar. I learned a lot about the history of Bangladesh as well. The following is what I found…

Banglandesh history

The early history of the Bengal region featured a succession of vast Indian empires, often accompanied by internal strife, and a struggle between Hinduism and Buddhism for dominance. Islam later made its appearance during the 8th century when Sufi missionaries arrived on the scene. Later, Muslim rulers paved the way for millions of new converts by building mosques, schools and social centers.

The first European power to arrive in India was the Macedonian army of Alexander the Great in 327–326 BC. Alexander appointed regional leaders in the northwest of India to govern in his absence, but his influence quickly crumbled after his armies were ousted from the Subcontinent. Later, trade between the various Indian states was established between the Roman Empire and India by Roman sailors who had reached India via the Red Sea and Arabian Sea, but the Romans never established permanent trading settlements.

The spice trade between India and Europe was one of the main avenues of trade in the world economy and was the main catalyst for the period of European exploration. Indeed, the search for a shorter, quicker access to India led to the accidental “discovery” of the Americas by Christopher Columbus in 1492.

Only a few years later, near the end of the 15th century, Portuguese sailor Vasco da Gama became the first European to re-establish direct trade links with India since those of Roman times by being the first to arrive by circumnavigating Africa (1497–1499). Having arrived in Calicut, which by then was one of the major trading ports of the eastern world, he obtained permission to trade in the city from Saamoothiri Rajah.

Trading rivalries among the seafaring European powers brought other European powers to India. The Dutch, England, France, and Denmark all established trading posts in India in the early 17th century. As the Mughal Empire disintegrated in the early 18th century, and then as the Maratha Empire became weakened after the third battle of Panipat, many relatively weak and unstable Indian states which emerged were increasingly open to manipulation by the Europeans, through dependent Indian rulers.

In the later 18th century Great Britain and France struggled for dominance, partly through proxy Indian rulers but also by direct military intervention. The defeat of the redoubtable Indian ruler Tipu Sultan in 1799 marginalized the French influence. This was followed by a rapid expansion of British power through the greater part of the Indian subcontinent in the early 19th century. By the middle of the century the British had already gained direct or indirect control over almost all of India. British India, consisting of the directly-ruled British presidencies and provinces, contained the most populous and valuable parts of the British Empire and thus became known as “the jewel in the British crown”.

British colonialism and the Bengal famines

A series of deadly famines were to hit the Bengal region of India–the last and most devastating was in 1941. It struck hard, killing more than 10 million men, women and children.

True, Britain was preoccupied with its own national survival during World War II, but Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s callous response to the suffering of the Bengali peoples was shocking.

British imperialism had long justified itself with the pretense that the colonization of India was conducted for the benefit of the governed. However in his recently published book The Ugly Britain, Shashi Tharoor disagrees. He documents disparaging remarks that seemed to be foundational to the thinking of British economists and politicians throughout the colonial period.

In doing so, Tharoor dampens our western idolatry of the late Winston Churchill. He says Churchill’s conduct in the summer and fall of 1943, during the peak of the last great Bengal famine, revealed the man’s true character.

He quotes Churchill as saying in a war-cabinet meeting to the British Secretary of State for India, Leopold Amery, “I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.” Churchill went on to dismiss the horrors of the famine, blaming the famine, not on British policies, but rather on the Indians for “breeding like rabbits.”

Modern Bangladesh

The borders of the modern People’s Republic of Bangladesh were established with the partition of Bengal and India in August 1947, when the region became East Pakistan as a part of the newly formed State of Pakistan. However, it was separated from West Pakistan by 1,600 km (994 mi) of Indian territory.

Due to political exclusion, ethnic and linguistic discrimination, as well as economic neglect by the politically dominant West Pakistan, popular agitation and civil disobedience eventually led to the war of independence in 1971 and the founding of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

After gaining independence, the new state would continue to endure food shortages and widespread poverty, as well as political turmoil and military coups.

The restoration of democracy in 1991 has been followed by relative political calm and slow economic progress; however, a third of this poor country annually floods during the monsoon rainy season, hampering economic development.

The population of Bangladesh is 142 million. That’s almost half the US population crowded into a land mass about the size of New York state.

Dr. Rashid Malik and family

I am welcomed to Bangladesh by my Bangladeshi friend Dr. Rashid Malik and his wife Yasmin Malik, founders of Malik College in Atlanta, Georgia. This was my first visit to Bangladesh, so it was reassuring to be met by someone who was very familiar with this relatively new nation and its political goings on.

Rashid’s older brother Malik Abdullah Al-Amin (“Sadi”) is a judge in the Bangladesh Judicial Service. Sadi, his parents and the rest of Rashid’s family have played an important role in the formation of this relatively new nation.

Rashid’s father, Advocate Abdul Wadood Malik, was a lawyer for the Supreme Court of Pakistan and continued in that position in the Bangladesh Supreme Court after Bangladesh won its independence from Pakistan . His mother Momtaz Begum Malik is the former principal of a prestigious college in Bangladesh. Today members of Malik family can be found in various parts of the world: the US, Sweden, India, Kuwait, and the United Kingdom.

Rashid is very proud now to be an American citizen. He tells me, “I am now the president of Malik College in Atlanta. This is my family’s way of giving back to the USA for what America has done for us. In short, the USA has given much to us in many ways, to me, to Yasmin and to my children.”

Travel to the far-south

Knowing of my interest in learning more about the history and persecution of Rohingya Muslims within the neighboring state Myanmar (formerly Burma), Judge Malik arranged flight tickets for Rashid, himself and me to travel south to Cox’s Bazar, on the Gulf of Bengal. In Cox’s Basar we were met by a private car and driver and taken south.

From Cox’s Bazar south are huge populations of Rohingya refugees who have fled persecution in neighboring Myanmar. A history of the Rohingya peoples and the cause of the appalling persecution will be discussed in detail in my next blog post about my travels to Myanmar and Thailand. Here we will address the issue of Rohingya refugees living in Bangladesh.

UN Rohingya refugee camps

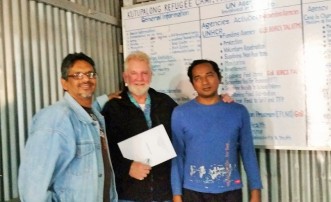

In many countries, when you reach the age of 21 you become an adult and must start to fend for yourself. But in the United Nations Dr. Rashid Malik, Sam and Kutupalong camp director Mohammed Ishmail. But 21 years after the Rohingya first started

arriving as refugees in Bangladesh, these desperately poor people are more dependent on aid than ever.

While these may sound like luxuries to an estimated 240,000 other unregistered Rohingyas living outside the camps and in the hills and local villagers in this poverty-stricken region, camp residents often lament the fact that their entire lives appear to be doomed to be living out as unsettled refugees.

There are mixed reactions to the official refugee camps.

Visiting the Kutupalong camp

“This is not life,” said Shaufiq Alam, a 30-year-old refugee in the Kutupalong camp. “I came 20 years ago. If I had been in the village I could have received a higher education by now. The camp situation is depriving us of our lives.”

The UN refugee agency is working to change that sense of powerlessness, but within tight operational constraints. It works closely with refugee-elected camp management committees, empowering them to mediate disputes and organizing women’s training and peace education workshops.

Refugees are also encouraged to participate in the day-to-day running of the camps. Bibi Begum, 30, helps to distribute food rations in Kutupalong every two weeks. Today she is in charge of sugar, stirring a sack sugar with her hand to loosen the grains before spooning precise portions into waiting plastic bags.

A widow with three children, she is one of seven incentive workers at the food distribution center who are given employment.

“I get 1,820 taka (US$22.50) per month. It helps with the children’s school supplies, and I can buy extra things,” she said. “Usually I make fishing nets for a living, but it is not profitable. I only made 1,000 taka after three months of work.”

The UNHCR vocational training is another important empowerment tool. While the refugees are not permitted to work or to sell things they produce, UNHCR seeks to keep them occupied while teaching them skills like carpentry, soap making and tailoring that they can hopefully use in the future.

At Nayapara camp, Hamida Khatun, a 40-year-old widow with five children, is busy making soap. “I wanted to earn some money so I approached UNHCR to put my name on the list,” she said. “I’ve been doing this for a month, learning how to mix chemicals and use the mould.”

Her job today is to cut individual bars of soap to make sure they weigh a consistent 150 grams each. “I am proud of my soaps,” she said. “I get 1,036 taka per month for six months. But it’s not enough. There are 14 people in my family – six are registered and get food rations, the rest are not registered and get nothing. The money helps to buy some extra rice, but it is not enough for extra blankets.”

When completed, Hamida’s soaps are taken to the Bangladeshi Red Crescent Society to be distributed in the camp’s Women’s Centre along with some underwear, clothing and other personal items.

The clothing items are made at the Nayapara Women’s Centre by refugees attending the tailoring class. “They are usually aged 15 to 25, and rotate every six months,” said one of the women in charge. “We teach them skills and keep them busy so hopefully they don’t get married off at a young age.

Economic disadvantages

Unfortunately, there are few prospects after the six-month training as most refugees cannot afford to buy their own equipment. Even those who manage to buy a sewing machine find it hard to get raw materials and to market their products. Without regular practice, their skills fade quickly.

In comparison, the more than 240,000 unregistered Rohingyas living outside the camps appear to have developed their own coping mechanisms over the years.

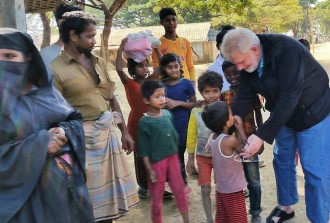

I am shocked at the sight of thousands of young children, 8 to 10 years old, wandering the roads or working in the markets, many without parents. The roadside markets are busy and these children have found informal ways to survive without government or UNHCR support. I am told that many have resorted to “sordid ways” of subsistence. I inquire further. It is said some of these Rohingya children are falling prey to human trafficking and heroin trade. Many of these Rohingya children have little or no knowledge of the Islamic faith that once guided them morally.

These problem lead one to believe that we need rethink how best to help these stranded refugees.

“The UNHCR is good at emergency response, setting up camps quickly in the hope that refugees can return in one to two years,” said Dirk Hebecker, head of the agency’s sub-office in Cox’s Bazar. “But when the situation gets protracted, we need to be able to adjust our strategies.”

He added that the international community should work with the Bangladeshi government to shift from focusing on just the two camps—which currently cares for only 10 to 15 per cent of the refugee population. He says the whole refugee population, including those outside the camps, must be immediately assisted if practical solutions are to be found to this long-running catastrophe.

Young children 9 to 15 years of age are seen wandering the streets. We learn that many of their mothers and fathers were killed in Myanmar or have died from disease and starvation during their exodus en route to Bangladesh.

In the following 5-minute video you will hear testimonies about the nearly 300,000 Rohingya refugees now living in Bangladesh.

POST YOUR COMMENTS