A Muslim voice for peace

MVPR announced in Washington, DC

Muslim Voice for Peace & Reconciliation (MVPR) made its debut on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, at a luncheon on Tuesday, April 7, 2015. “This was the public announcement of our human rights work,” says Samuel Shropshire, MVPR founder. “I am grateful for the advice and encouragement of all who attended.”

Shropshire was accompanied to Washington by Suhaib Mallisho of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Present at this important meeting were leaders from numerous humanitarian non-government organizations that are already advocating for human rights and world peace in the US capital.

Among attendees of the MVPR-sponsored luncheon, were Diane Randall,Friends Committee on National Legislation; Lisa Sams, Middle East Sub-Committee/Global Missions Committee of St. Albans Episcopal Church; Richard Parkins, Friends of the Episcopal Church of South Sudan; Stephanie Kinney, former diplomat with the US Department of State; Thomas Johnson, Companion Diocese of Jerusalem; Nate Hosler, Office of Public Witness,Church of the Brethren; Sayyid Syeed, Islamic Society of North America; Ambassador Warren Clark, Churches for Middle East Peace; and Raed Jarrad, Policy Impact, American Friends Service Committee.

Shropshire and Marina Buhler-Miko, acting MVPR chief operations officer, presided over the meeting.

“Washington, DC, is an important city. MVPR advocacy has found a lot of friends here,” Shropshire said.

Shropshire says, MVPR will do its best to let the American people know that Islam cares about human rights and all peoples facing oppression and injustice. He says, “MVPR will collaborate with Jewish, Christian and other religious and secular groups that seek to relieve the world of human misery.”

“We are Muslim men and women who care about others, regardless of their faith tradition,” he said. “And in that capacity we will seek to ally with others who have the same mission to change the world for the better.”

Shropshire also met with Patty Johnson, Canon Missioner for Outreach of theWashington National Cathedral, and Grace Said, Chair of the Cathedral’sPalestine-Israel Advocacy Group.

Shropshire said MVPR is seeking to provide leadership in peacemaking and human rights, especially in the Middle East. He emphasized that political and religious reconciliation is of utmost importance since, today, many faiths have been divided and hijacked by radical elements.

Shropshire has been living in the Mecca Region of Saudi Arabia for the past three years. He believes that the Abrahamic faiths, working in solidarity, hold the key to solving many of the world’s problems.

“One thing is certain,” he says. “No one will gain from a violent war that seeks to pit Muslims, Christians and Jews against each other. Working together we can end the conflicts and find a better way.”

The history of human rights

Shropshire points out that today is an age that is striking in its unprecedented technological sophistication and many advances. “But unfortunately, the prejudices and inequities that have plagued the human race for millennia continue to exist, and are responsible in our day for untold human suffering.”

Throughout history, especially in the Middle East, there have been individuals who have stood up for the rights of others.

Shropshire insisted, “We must ensure that these God-ordained rights are guaranteed to all the world’s citizens? There can be no exceptions.”

Shropshire says there is a firm foundation that has been established for all mankind–beginning in the Middle East with Cyrus the Great’s cylinder and the Prophet Mohammad’s Constitution of Medina, followed by the British Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights as enshrined within the United States Constitution, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the eventual Geneva Convention that laid the groundwork for the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Here is some detail about each of these human rights documents in the order of their appearance:

Cyrus the Great and his Akkadian language cylinder

In 539 BC, the armies of Cyrus the Great, the first king of ancient Persia, conquered the city of Babylon. But it was his next actions that marked a major advance for all humankind. He freed the slaves, declared that all people had the right to choose their own religion, and established racial equality. These and other decrees were recorded on a baked-clay cylinder in the Akkadian language with cuneiform script.

Known today as the Cyrus Cylinder, this ancient record has now been recognized as the world’s first charter of human rights. It has been translated into all six official languages of the United Nations, and its provisions parallel the first four Articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

From Babylon, the idea of human rights spread quickly to India, Greece and eventually Rome. In Rome the concept of “natural law” arose, in observation of the fact that people tended to follow certain unwritten laws during the course of life, and Roman law was based on rational ideas derived from the nature of things.

Islam, human rights and the Constitution of Medina

To the surprise of many, another early attempt at formally enumerating human rights is the Charter of Medina, also known as the Constitution of Medina. It was drafted by the Islamic prophet Muhammad (pbuh) shortly after his arrival at Medina in 622 AD, following the Hijra (immigration of Muslims) from Mecca to Medina.

The charter constituted an agreement between the various native Muslims of Medina (the Ansar), the Muslim immigrants from Mecca (the Muhajarun), Jewish believers, Christian groups in Medina and even pagans, declaring them to constitute ummah wāḥidah (“one nation”). The Constitution formed the basis of a multi-religious Islamic state in Medina.

The Constitution of Medina was created to end the bitter inter-tribal fighting between the rival clans of Banu Aws and Banu Khazraj in Medina, and to maintain peace and cooperation among all Medinan groups for fashioning them into a cohesive society. It ensured freedom of religious beliefs and practices for all citizens. It assured that representatives of all parties, Muslim or non-Muslim, should be present when consultation occurs or in cases of negotiation with foreign states, and that no one should go to war before consulting the Prophet. It also established the security of women, a tax system for supporting the community in times of conflict, and a judicial system for resolving disputes. It declared the role of Medina as a ḥaram (“sacred place”), where “no weapons can be carried and no blood spilled.”

The Constitution of Medina serves as an example of finding resolve in a dispute where peace and pluralism were achieved, not through military successes or ulterior motives, but rather through an agreed upon mutual respect, acceptance, and denunciation of war – aspects that reflect some of the basic tenets of the Prophet Muhammad’s (pbuh) own faith and commitment to God. These guiding principles of early Islam brought peace and stability to Medina. Religious pluralism and friendship and mutual respect were the law of the land!

A careful study of this document could help avoid many of the divisions and misunderstandings plaguing the world today. The principles embodied in the Constitution of Medina could easily be used to unite Muslims, Christians, Jews and peoples of other faiths.

The Constitution of Medina not only guaranteed the equal rights and protections of all citizens (Muslims, Christians and Jews), it spelled out the only conditions of what could be considered legal defensive just wars and the proper military conduct during the conduct of defensive war. (Offensive war was considered illegal and un-Islamic.)

Islam’s early contribution to human rights is best appreciated when viewed against the backdrop of world history as well as the realities of modern times.

As in all times, greed, prejudice and hate drive nations to war and conflict. Economic and social disparities have resulted in the oppression of poorer populations; racial prejudices have been the cause of subjugation and enslavement of people with darker skin; women have been weighed down by chauvinistic attitudes, and pervasive attitudes of religious superiority have led to widespread persecution of people with different beliefs.

“However, when considering the question of human rights and Islam,” declares Shropshire, “it is important to distinguish the divinely prescribed rights promoted by Islam from potential misinterpretation and misapplication by imperfect human beings.”

“Just as Western societies still fight against racism and discrimination, many Muslim societies continue to struggle to fully implement human rights as outlined in Islam,” he says.

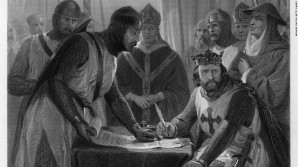

The English Magna Carter

Magna Carta, meaning ‘The Great Charter’, is one of the most famous documents in the world. Originally issued by King John of England(r.1199-1216) as a practical solution to the political crisis he faced in 1215, Magna Carta established for the first time the principle that everybody, including the king, was subject to the law. Although nearly a third of the text was deleted or substantially rewritten within ten years, and almost all the clauses have been repealed in modern times, Magna Carta remains a cornerstone of the British constitution.

Most of the 63 clauses granted by King John dealt with specific grievances relating to his rule. However, buried within them were a number of fundamental values that both challenged the autocracy of the king and proved highly adaptable in future centuries.

Most famously, the 39th clause gave all ‘free men’ the right to justice and a fair trial. Some of the Magna Carta’s core principles were written into in the United States constitution in the form of the Bill of Rights and in many other constitutional documents around the world, as well as later in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights.

The United States Constitution

The American democracy and its constitution is a foundation stone for a long tradition of human rights and personal freedoms.

Written during the summer of 1787 in Philadelphia, the Constitution of the United States of America is the fundamental law of the US federal system of government and a landmark document of the Western world. It is the oldest written national constitution still in use and defines the principal organs of the US government, describing the balance of powers of the legislative government (President, Congress and the Supreme Court), outlining their jurisdictions and the basic rights of American citizens.

The early establishment of American human rights laws was in no way perfect as slavery and discrimination against African Americans, Native Americans and other minorities would persist for decades, but the US Constitution would lay the groundwork for an evolving, more humane nation.

The Bill of Rights were incorporated as an important part of the US Constitution, protecting the basic freedoms of all American citizens.

These human rights came into effect on December 15, 1791, limiting the powers of the federal government of the United States and protecting the rights of all citizens, residents and visitors within American territory.

The Bill of Rights protects freedom of speech, freedom of religion, outlines the right to keep and bear arms, the freedom of assembly and the freedom to petition the government. It also prohibits unreasonable search and seizure on private premises. “Cruel and unusual punishment” was strictly forbidden, and it outlawed compelled self-incrimination.

The Bill of Rights prohibits the government from making any law “respecting an establishment of religion” and prohibits the federal government “from depriving any person of life, liberty or property” without due process of law. In federal criminal cases it requires indictment by a grand jury for any capital offense, or infamous crime, guarantees a speedy public trial with an impartial jury in the district in which the crime occurred and prohibits double jeopardy.

France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man

The inspiration and content of this document emerged largely from the ideals of the American Revolution. The key drafts were prepared by theMarquis de Lafayette, working at times with his close friend Thomas Jefferson. In August 1789, Honoré Mirabeau played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on 26 August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly, towards the end of the French Revolution. It was the first step toward writing a constitution for France. Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the declaration was discussed by the representatives on the basis of a 24 article draft.

The draft was later modified during the debates. A second and lengthier declaration, known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793, was written in 1793 but never formally adopted.

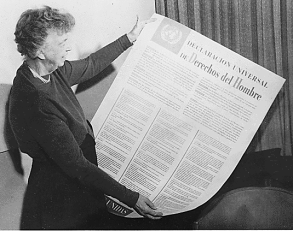

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

With the end of World War II and the creation of the United Nations, the international community vowed never again to allow atrocities like those of that international conflict to ever happen again.

World leaders decided to complement the UN Charter with a road map to guarantee the rights of all peoples. The document they considered, and which would later become known as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, was taken up at the first session of the General Assembly in 1946. The Assembly reviewed this draft Declaration on Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms and transmitted it to the Economic and Social Council “for reference to the Commission on Human Rights for consideration.

The Commission, at its first session early in 1947, authorized its members to formulate what it termed “a preliminary draft International Bill of Human Rights”. Later the work was taken over by a formal drafting committee, consisting of members of the Commission from eight States, selected with due regard for geographical distribution.

The Commission on Human Rights was made up of 18 members from various political, cultural and religious backgrounds.

Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, chaired the Universal Declaration of Human Rights drafting committee. With her were René Cassin of France, who composed the first draft of the Declaration, the Committee Rapporteur Charles Malik of Lebanon, Vice Chairman Peng Chung Chang of China, and John Humphrey of Canada, director of the UN’s Human Rights Division and preparer of the declaration’s blueprint. Eleanor Roosevelt was recognized as the driving force behind the declaration’s eventual adoption.

The final draft, presented by Cassin, was handed to the UN Commission on Human Rights in 1947, which was being held in Geneva.

The entire text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was composed in less than two years. At a time when the world was divided into Eastern and Western blocks, finding a common ground on several points proved to be a colossal task.

The unfinished work of championing peace and human rights

During the 20th century a number of great individuals have made their mark on human rights. Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton crusaded for women’s suffrage in the United States. Mahatma Gandhi in India was most effective in gaining India’s independence and championing the rights of Indian citizens. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, brought an end to segregation in the United States and Nelson Mandela was greatly used to dismantle apartheid in South Africa,

Many other men and women have stood up at various times, against all odds, to champion world peace and human rights. And, today, 21st century activists are answering the call.

Take a few minutes to learn more. Watch this short United Nations video about the incredible history of human rights:

Sources: United Nations, Encyclopaedia Britannica, wikipedia.org, US Library of Congress, A History of England, Oxford Bibliographies, Notes in History, humanrights.com, Youth for Human Rights

1 Comment

Hosting

A most interesting series you’ve put together, Sam starting with the Muslim constitution of Medina. Hi Jeff, Just happened to stumble on your website and was a bit taken back, since I expected you to still be involved with the Persecuted Church.